Why Is 0 Called Love in Tennis? The Quirky History Explained

You see the word ‘love’ thrown around at every tennis match when the score hits zero. At first, it sounds sweet and maybe romantic—but there’s nothing warm and fuzzy about having a big fat zero on the board. So why the heck do tennis players say ‘love’ instead of just… zero?

If you’re new to tennis, watching a match can feel like reading secret code. The scoring system itself is weird enough (who decided on 15-30-40?), and then we toss ‘love’ into the mix just to make things more confusing. But here’s the trick—understanding this one oddball word will make tennis suddenly way more fun to follow, whether you’re at a massive tournament or just hanging out at your local club.

‘Love’ has roots that go way back, and tracing its history is like digging into a family story you never knew you had. Some people think it’s about eggs, some point to old French words, and others think the whole thing started as a joke between early players. There’s actually more drama in the term than you might guess!

- The Basics of Tennis Scoring

- Where ‘Love’ Came From

- The Debated Origins: Egg or Love?

- How the Term Spread in Tournaments

- How to Use ‘Love’ When Watching or Scoring

- Fun Facts for Tennis Fans

The Basics of Tennis Scoring

If you’ve ever sat through a match, you know tennis scoring can look like a secret handshake among longtime fans. Let’s break down how it actually works, so you’re not lost by the second game.

The magic sequence in tennis scoring is 15, 30, 40, and game. It looks random, but it’s the standard everywhere, from neighborhood courts to Grand Slam finals. At the start of a game, both players start at 0, known as love. The first point gets you to 15, win another and you’re at 30, grab a third and now it’s 40. One more point wins the game, unless the players tie at 40 (called ‘deuce’), then someone needs to score two points in a row to take the game.

- Zero: Love

- One point: 15

- Two points: 30

- Three points: 40

- Four points: Game (unless tied at deuce)

If you’re watching on TV or at a tournament, you'll see the server’s score first. For example, if it’s “30-love,” it means the server has 30, and the opponent has zero.

| Points Won | Score Call |

|---|---|

| 0 | Love |

| 1 | 15 |

| 2 | 30 |

| 3 | 40 |

| 4 | Game |

Tennis matches are made up of sets, and sets are made up of games. In pro tournaments, men usually play best of 5 sets, while women play best of 3. To win a set, you need to take at least six games by a margin of two games. If things get super tight, you’ll see a tiebreak at 6-6. It sounds complicated, but once you follow a few games, it clicks. And trust me, knowing the lingo means more fun when you’re cheering during those intense rallies.

Where ‘Love’ Came From

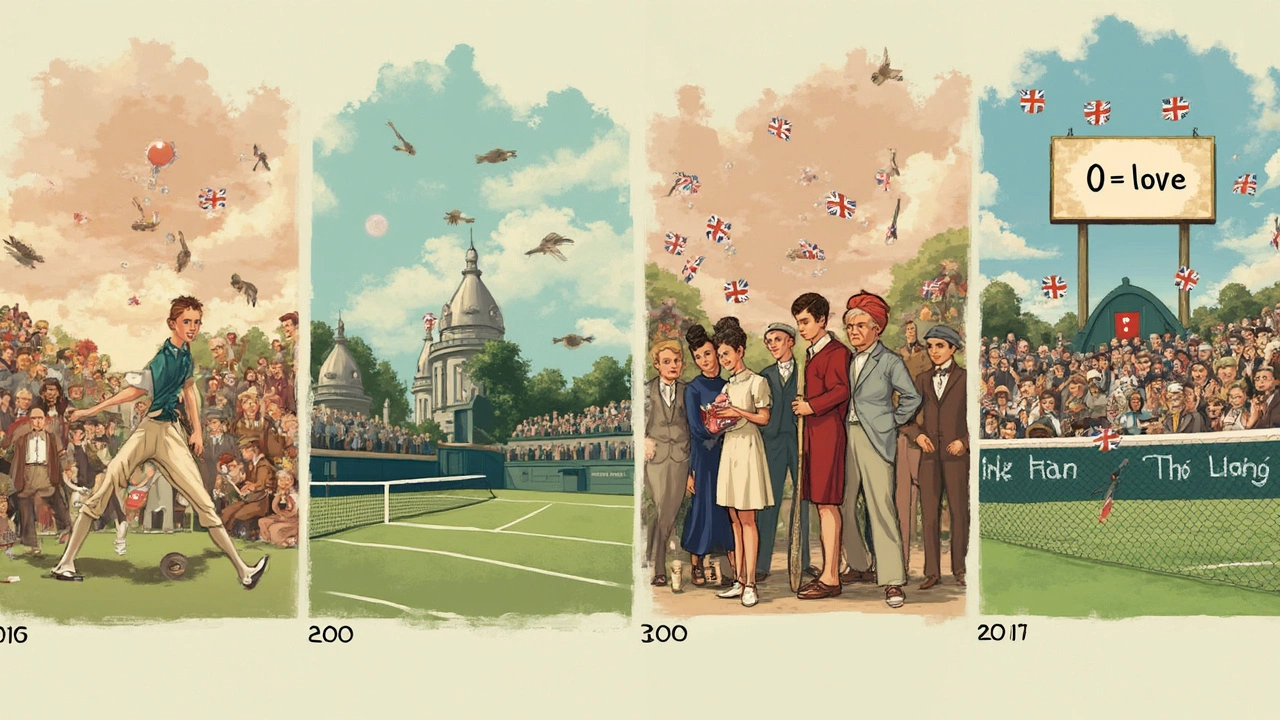

When it comes to tennis scoring, the use of ‘love’ for zero has confused just about everyone at some point. It didn’t just pop up randomly—the history actually has layers, and a lot of people have debated which story is true. Here’s what’s solid: one of the earliest and most popular theories points back to French tennis in the 16th century.

The French word for egg is “l’œuf” (pronounced kind of like 'luff'), because an egg and the number zero both look like a round shape. Early scorekeepers started using “l’œuf” as a catchy way to say zero. Then, as tennis spread to English-speaking countries, “l’œuf” got twisted into ‘love’ by players trying to copy the French, but doing it with a super English accent.

Another theory says ‘love’ comes from a saying about playing ‘for love’, meaning you play for the fun of it and not for money. People who had nothing to lose—nothing on the scoreboard—were playing for ‘love’. Even though it sounds sweet, there isn’t as much solid proof for this idea as there is for the egg one. Still, it’s a story that sticks with some old-school players, and it pops up at clubs all over the world.

Take a look at how the origin stories stack up side by side:

| Origin Idea | Main Support | Language |

|---|---|---|

| Egg Theory (“l’œuf”) | French slang, looks like zero | French to English transition |

| Playing ‘for love’ | Phrase meaning playing for nothing | English, general slang |

It’s kind of wild, but the egg story has the edge among most historians, especially since unique tennis terms often came through France before landing in English rulebooks. If you flip through old tournament texts or scorebooks, you’ll see ‘love’ being used way before the 1900s—even before tennis became big in the U.K.

The coolest part? Even though tennis rules have changed a bunch, ‘love’ has stuck around, confusing new fans, making little kids giggle, and giving tennis another odd detail you can explain the next time someone asks why the scoreboard doesn’t just say zero.

The Debated Origins: Egg or Love?

This is where tennis gets weird. The word ‘love’ in tennis might sound like affection, but the real story is about confusion and maybe a little bit of miscommunication over the centuries.

One of the oldest theories points to the French word “l’oeuf,” which literally means “the egg.” People figured zero kind of looks like an egg, so French players supposedly called a score of zero “l’oeuf.” British players, hearing this and not speaking great French, thought it sounded like “love,” and just ran with it. Seems silly, but words get mangled in sports all the time.

But not everyone agrees. Some historians think the use of ‘love’ comes from the phrase “to play for love,” meaning to play for nothing—no prize, just fun or pride. In this idea, when a tennis player has zero points, they’re supposedly playing for the ‘love’ of the game, not for any gain.

So, which story is right? Nobody’s 100% certain, but you’ll still find these two ideas pop up everywhere people talk about tennis. Here’s a quick breakdown of what’s floating around:

- Egg Theory: Comes from “l’oeuf” (French for egg), because zero looks like an egg. Brits copied it, morphed into ‘love.'

- Love of the Game: Refers to playing for nothing but enjoyment—a zero score meant you were just playing out of passion or pride.

Tennis authorities like the International Tennis Federation still use ‘love’ for zero, but there’s never been an official declaration about which origin is it. Both theories show up in books and articles, and casual fans debate it at every level—from Wimbledon all the way to high school matches in the U.S.

| Theory | Main Idea | First Appearance |

|---|---|---|

| Egg Theory | ‘Love’ came from the French word “l’oeuf” (egg) | Late 1800s (British tennis adoption) |

| Love of the Game | Zero points = playing for nothing, just for ‘love’ | Referenced in English club rules, late 19th century |

Honestly, both ideas kind of work, and it’s fun trivia to toss out when someone asks why you’re cheering for ‘love’ in the stands.

How the Term Spread in Tournaments

Once the word ‘love’ started popping up in local tennis games, it didn’t take long to show up in official tournaments. In the late 1800s, as tennis tournaments got organized in England and France, scorekeepers needed a consistent way to call out zero. ‘Love’ was easy to say and even easier to remember. When the first Wimbledon tournament rolled around in 1877, the word was already being used out loud by players and officials.

French championships, like Roland Garros (which turned into the French Open), had their own flair for language. They stuck to ‘zéro’ for a while, but British tournament officials and the international tennis crowd kept saying ‘love.’ It quickly became part of that shared tennis lingo that fans and players everywhere could understand, no matter what country the match was in.

Rules committees and organizations like the Lawn Tennis Association (LTA) published the official tournament scoring guides during the early 1900s—and ‘love’ was right there in black and white. Even the International Tennis Federation (ITF) used it, so as the game went global, everyone heard zero as ‘love’ no matter where the match took place.

| Year | Tournament | Scoring Language |

|---|---|---|

| 1877 | Wimbledon (UK) | Love |

| 1891 | French Championships | Zéro/Love* |

| 1900s | US Open & Australian Open | Love |

*The transition from ‘zéro’ to ‘love’ in France happened gradually as British scoring became international standard.

- The use of ‘love’ meant fewer mix-ups for scorers, players, and fans.

- By mid-20th century, every major tennis tournament had standardized the term.

If you’re at a tennis event and hear “fifteen-love,” you’re hearing over a century of tradition still going strong. There’s history woven into every call from the umpire’s chair—and now you know exactly where it came from.

How to Use ‘Love’ When Watching or Scoring

So you're watching a match and hear “fifteen-love” or “love-forty.” Here’s what’s happening—‘love’ always stands for zero, plain and simple. Any time a player hasn't scored a single point in a game, their side of the score gets called ‘love.’ The first number said always belongs to the server. So if the score is announced as "love-30," it means the server hasn’t won a point yet, but their opponent has won two. Simple, right?

Understanding tennis scoring at tournaments or on TV gets easier once you spot this pattern:

- “Love” is always zero—no exceptions, no weird special cases.

- The server’s score is listed first. So “love-15” = server has zero, receiver has one point.

- You’ll hear “love” in every single set. There’s no alternate term, even in major tournaments like Wimbledon.

Here’s a quick cheat sheet for the possible "love" scores you’ll hear in a single game:

| Term Called | What It Means |

|---|---|

| Love-fifteen | Server has 0, Receiver has 1 point |

| Love-thirty | Server has 0, Receiver has 2 points |

| Love-forty | Server has 0, Receiver has 3 points |

| Fifteen-love | Server has 1, Receiver has 0 points |

| Thirty-love | Server has 2, Receiver has 0 points |

| Forty-love | Server has 3, Receiver has 0 points |

Pro tip: If you’re scoring for friends at your local club, just say 'love' for zero—the tradition stretches from backyard games all the way to grand slam finals. You don’t have to announce any special rules or use a different word, no matter the level. If a set starts out, and nobody has scored yet, the umpire: “love-all,” meaning both players are at zero.

Knowing this actually helps you follow the flow of a match without getting lost. You’ll never have to wonder who’s ahead if you just watch which side the ‘love’ lands on. Pop quiz: If you hear “thirty-love,” you already know which player is having a good game, right?

Fun Facts for Tennis Fans

So you love tennis, or maybe you’re just getting hooked—and the wacky scoring isn’t the only thing catching your eye. Here’s the stuff you can use to impress your friends, or just drop as casual trivia during the next match. Because, honestly, who doesn’t love a good story behind what you see on court?

- The word ‘love’ for zero isn’t used in any other major sport. You won’t find football, basketball, or even badminton using it—tennis does its own weird thing and just rolls with it.

- This bit might surprise you: The official rulebooks for tennis don’t even bother explaining ‘love’—it’s just assumed that if you play or watch, you’ll figure it out. The USTA and ITF just stick with ‘love’ on the score sheet and move on.

- Some tournaments, especially in the 1800s, tried using “nil” instead of “love.” It never caught on outside of a few stuffy British clubs who thought it sounded more proper. Players quickly stuck to what felt familiar.

- Famous players have sometimes joked about the term. Serena Williams has pointed out in interviews that while love means zero in tennis, her drive on court is anything but—she’s all in, never zero effort.

- “Double bagel” is the slang for when you win a tennis match 6-0, 6-0. The zeros look like bagels, obviously, but it’s also a playful nod to how common ‘zero’ is in tennis language—whether you call it love or breakfast food.

One last tip: If you ever keep score in a casual match, it’s totally normal to use “love all” for the start of a game (meaning 0-0), and people will think you’re a seasoned tennis buff. Don’t worry, even if you mix up the terms, it happens to the pros and commentators sometimes, too. Just have fun with it—that’s half the game.